Signature Jewelry from Bonnie Hedden Designs Capture the Eye with a Sparkle

September 13, 2025

New York Lawyer-Turned-Artist Captures Familiar Moments with a Brush

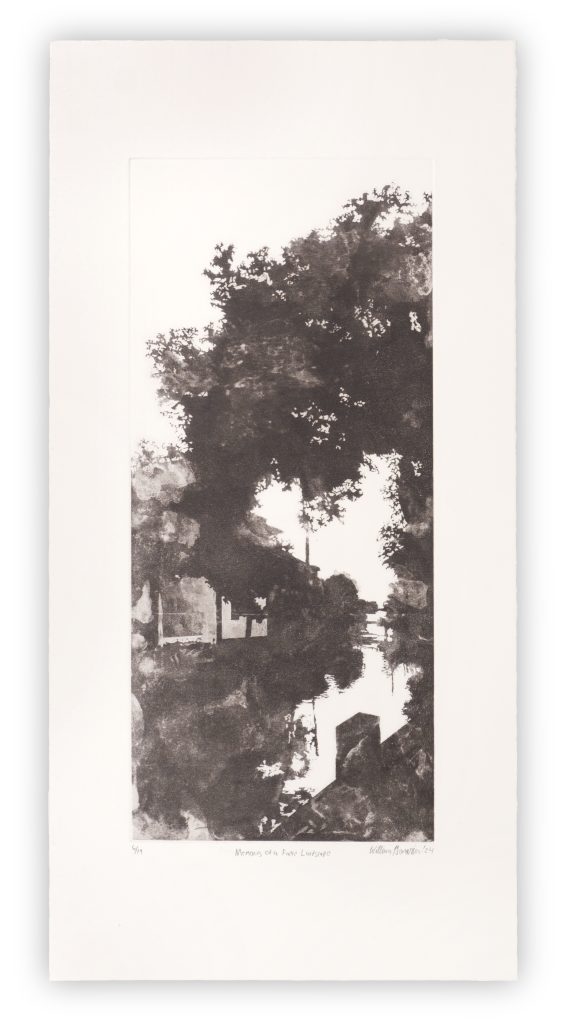

November 11, 2025 When a memory lingers with William Demaria, he doesn’t reach for a sketchpad or a paintbrush.

When a memory lingers with William Demaria, he doesn’t reach for a sketchpad or a paintbrush.

The Baltimore artist starts with a Sharpie and a piece of copper, his initial tools to begin his unique process of intaglio printmaking. The technique creates images by incising lines or areas into a metal plate. Printing the image relies on the pressure of a press into those incised lines to pick up the ink.

It’s an ancient art that continues to play a role in today’s paper currency, which relies on digital engraving for its imagery. As much as intaglio printmaking is an integral part of our society, “Very few people know how to do it,” said William, another of the reasons he was moved to make a career of it.

The sculptural quality of carved copper plates reminds him of experiences he had observing the Earth carved by glaciers. He is intrigued by the material culture of how things existed hundreds of years ago and just as significantly, how those things are remembered today.

“My direct inspiration comes from memories,” William said. “Certain things in the landscape stay with you for a long time.”

If Williams walks by something and three months later, it remains etched in his memory, he’s found a new subject. Often it’s something in the natural world.

“Nature is a really good medium for having conversations about human emotion,” he said. “I’ve always had a strong emotional response when going on a hike and coming across a tree that’s fallen across a river. To me, those are emotional things.”

A recent walk around the Baltimore Harbor caught his eye for the beauty in the landscape. On the other hand, Williams finds a different kind of beauty in train stations, their warm urban concrete combined with the idea of people moving through them to transport to another place.

As a youngster in Long Island, William was drawn to history. “I actually grew up in a family of Civil War re-enactors,” he said.

As a student at Cornell University, he sought a way to connect history and art. An art teacher handed him what he calls a “funny shaped chisel,” and William’s journey into printmaking began.

“People really stopped doing this process a couple hundred years ago,” said William, who earned a Bachelor of Fine Arts in 2020. “To actually study it, I spent a lot of time reading about French people in the 1700s and their strong opinions on how to carve metal.”

William has had a lifelong fascination with German printmaker Albrecht Dürer, among the greatest artists of the Northern Renaissance. Dürer created cut metal plates for engravings, a laborious art form that reached its technical height in the 17th century. He used those engravings as a basis to create hybrids of printmaking and painting called monoprints.

After graduation, William worked in a fine art print publishing company in New York, where he learned to refine the aspects of publishing the plates. The creative energy to produce his own images grew inside of him. The warehouse work allowed him to hone his skills in professional presentation.

“Even not ruining them when you’re transporting them is a really big thing when you’re working on paper,” he said.

If possible, William starts his process by returning to the site that stuck in his memory and uses a Sharpie and piece of copper to draw it. Or he will create it from the details that are vivid in his mind.

From there, he uses a chisel to trace the Sharpie lines into the copper. “That’s how you arrive at your carving or your engraving in the copper, which you use as the basis for your monoprints,” he said.

The carved lines hold ink so when it runs through a press with a piece of paper, that ink is removed. The linework carved into the plate becomes the sculptural foundation that create paintings with the ink on top of them.

“When you run it through the press, the engraved lines and these painted marks are transferred onto paper,” he said.

William prefers to work in black and white. Color doesn’t resonate as much with his memory; black and white keeps it authentic. His work has become increasingly more minimal.

“Originally I was making artwork about reality,” he said. “The shift in my work has been making art about how I remember reality.”

William has become more thoughtful about the final form of presentation, which he used to focus on after a piece was complete. Now he is consciously thinking about it the whole way through. He does all the woodworking to make his frames.

William started showing at New York shows and has since added others, including Rose Squared Art Shows. Visit his booth and he’ll likely have a piece of copper in hand. He enjoys demonstrating the process and explaining its roots to customers.

William started showing at New York shows and has since added others, including Rose Squared Art Shows. Visit his booth and he’ll likely have a piece of copper in hand. He enjoys demonstrating the process and explaining its roots to customers.

Unlike the traditional way of carving copper, he keeps his flat on a table while using his carving tool. William also favors inconsistent impressions that he refers to as “closer to a hybrid of painting than resembling a print.” Shining light on the finished work reveals the ridges of the engraved lines, which gives his artwork a subtle, three-dimensional quality.

Look for William’s booth at Rose Squared Art Shows, including Fall Brookdale Park (Oct. 18-19, 2025).